In case you haven’t seen it, there are three parts

to each show: the Signature Challenge, the Technical Challenge, and the

Showstopper Challenge. For the first and last challenges, they plan their own

version of whatever has been assigned (“please make Paul and Mary sixteen

perfect petits fours, in two flavors”, e.g.). Some contestants come up with very

unusual flavor combinations, which makes me wish I could taste their results as

well as see them.

The Technical Challenge is different. The

contestants are all given the same recipe and ingredients, and left to do the

best job they can. Usually the recipe is for something that few of them have

ever made before, and sometimes it’s a pastry that none of them have even heard

of. On top of that, the recipe is deliberately skimpy on details—the temperature

for the oven, but not the baking time, for instance. Recipes for yeast-raised

dough tend to leave out rising times, and sometimes parts of the recipe just

say, “Make a custard” or “Prepare fruit”, leaving the contestant to fill in the

gaps with their own knowledge of baking (and some on-the-spot guesswork.)

And that’s why I love the Technical Challenge. It’s

a test of their overall baking know-how. The more broadly they have experimented

in baking and the more they have read about different baked goods, the more likely

they are to know something about baking the assigned item. Being practiced in common techniques helps when the recipe leaves

out the details. Even being inquisitive in sampling pastry can pay off— if the

contestant has eaten the pastry in question, at least they have some idea how

it should turn out.

And that’s why I love the Technical Challenge. It’s

a test of their overall baking know-how. The more broadly they have experimented

in baking and the more they have read about different baked goods, the more likely

they are to know something about baking the assigned item. Being practiced in common techniques helps when the recipe leaves

out the details. Even being inquisitive in sampling pastry can pay off— if the

contestant has eaten the pastry in question, at least they have some idea how

it should turn out.

Now onward to Cakes

For Bakers, a cookbook for the professional baker, copyright 1923. This

book belonged to my Grandpere, who was, indeed, a professional baker. The book

in interesting for a number of reasons. It’s old and refers to things like “pastry

butterine” and whether the damper should be closed while baking. The selection

of recipes is unlike my household cookbooks—it includes “Monte Carlos”, “Stork’s Nests”,

and various kinds of Zwieback and honey cake, for example. It offers

suggestions on pricing, decoration, and display of goods, and discusses the use

of ammonium carbonate in leavening cookies.

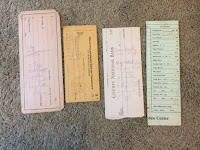

The most interesting part of the book, however, is

not the book itself but the multitude of scraps of paper that have been tucked

into it. Scrawled in pencil on the backs of old checks and garden store forms are

recipes—lists of ingredients, really—with no explanation of their existence. In

at least one case, my grandfather appears to be copying out a recipe from the

book for a butter cookie, but with less lemon. Are these notes on how to vary

existing recipes? Recipes from other books? Some appear to be calculations for

making a different size batch.

The most interesting part of the book, however, is

not the book itself but the multitude of scraps of paper that have been tucked

into it. Scrawled in pencil on the backs of old checks and garden store forms are

recipes—lists of ingredients, really—with no explanation of their existence. In

at least one case, my grandfather appears to be copying out a recipe from the

book for a butter cookie, but with less lemon. Are these notes on how to vary

existing recipes? Recipes from other books? Some appear to be calculations for

making a different size batch.

One thing is certain—there is no explanation of how the listed ingredients are to be mixed and

baked. To use these scrawled recipes, a person would either have to know the

technique, or look up a similar recipe and work from its instructions.

For a long time before I had this book, I was

trying to find a recipe for a certain kind of cookie that Grandpere made. All

through my childhood, when we stayed with them, we ate these cookies which were

stored in an old coffee can. There were crescents, ovals with scalloped edges,

and leaf-shapes, but they all seemed to be basically the same cookie with different toppings—chopped

nuts, tiny chocolate chips, whole cashews, or red candied fruit. My father said

much later that they were butter cookies, but the butter cookies I tried never

tasted quite right.

Eventually I found a butter cookie recipe with a

bit of almond flavor that seemed

right—but by then it had been so long that the flavor of the cookie was a dim

memory. Still, it seemed possible that the cookies might have had a touch of

almond—he put almond in the apple pastry and sliced almonds on the sides of

cakes. (I wish I had asked my father whether Grandpere was especially fond of

almond flavor. It’s too late now.)

So I was excited when I discovered the cookbook some years ago with its scraps of

recipes. Could the answer be here? Maybe the recipe for the butter cookie with

lemon? (Though I don’t remember any hint of lemon in the cookies he made.)

At least that list of ingredients matched with a recipe in the book, which would help with mixing directions.

The recipe in the book, however, was less than detailed. “Mix

like cakes?” How much is “as much ammonia as will lie on a dime?” (I had to

look up bakers’ ammonia and an equivalent in baking powder.) Finally, I guessed

at the temperature of the “moderate oven” and the time.

The recipe in the book, however, was less than detailed. “Mix

like cakes?” How much is “as much ammonia as will lie on a dime?” (I had to

look up bakers’ ammonia and an equivalent in baking powder.) Finally, I guessed

at the temperature of the “moderate oven” and the time.

The result, as I recall, was not remarkable. The

failing could be in the recipe or in my memory of the cookies or both. But the

challenge was an interesting one, and I think about it sometimes when I watch

the contestants on the Baking Show attempt to figure out their sketchy

instructions, and again when Paul and Mary survey the assorted results and compare

them to the picture-perfect version they’ve just been sampling in another tent.

If only I had a Chock Full O’Nuts can filled with

Grandpere’s cookies for the purpose of comparison, I could figure out that recipe

yet.